NUDIST HISTORY

This essay was written for presentation at the annual conference of the Organization for the Study of Communication, Language, and Gender on October 10, 2003 in Ft. Mitchell, Kentucky (hosted by the University of Cincinnati).

Reprinted with permission. No further reproduction permitted without the express permission of the author.

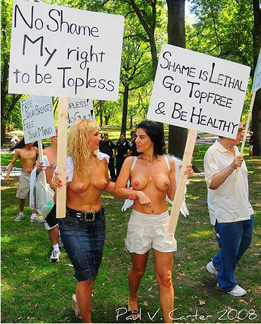

Top Freedom In The United States

One of my biggest fantasies is just to ride down the highway bare-breasted on my motorcycle. I resent the fact that men do not have to wear shirts and women do, especially in the summer when it's so hot.(Ayalah & Weinstock, 1979, p. 122)

It was probably a good thing for those children at the pool to see women's breasts as much as they wanted to and to be done with all the mystique, this hide-and-seek with women's breasts is obviously unnatural and everybody suffers in some way, especially women.(Ayalah & Weinstock, 1979, p. 128)

On the smoldering summer evening of June 21, 1934, everything seemed normal at Coney Island in New York City. The beach was crowded with men, women, and children dipping into the water after a long day at work. Somewhere in this scene, a group of men decided to remove their bathing tops and perform calisthenics on the beach. The next day, The New York Times reported the scandalous incident. This was the second day in a row that men had refused to cover their chests in public (Heat,

1934, p. 3).

The men were arrested and rushed to the county courthouse. Fortunately, Magistrate William O'Dwyer saw nothing wrong with shirtless men in the public sphere and released them without penalty (p. 3). To this day, the ease with which these men earned the right to go topless stands in stark contrast to the efforts put forth by members of the opposite sex. For instance, sixty years later a woman went to jail for going bare-breasted in the Osceola National Forest (Latteier, 1998, p. 161).

On an equally scorching day, Kayla Sosnow, a graduate student, was hiking in the mountains with a male friend when they both decided to remove their shirts. Two forest rangers spotted the pair and demanded that Sosnow cover her chest. She refused to do so. Later, she said, I knew it was ridiculous that men had the right to go without a shirt and women didn't, so I was going to do something about it, which was just take my shirt off and be comfortable

(p.161). Revealing her breasts in 1996 cost her four days in a Florida jail before she was allowed out on bail. Then, she: was found guilty of disorderly conduct and sentenced to thirty days in jail to be suspended after successfully serving five months probation, fifty hours of community service, payment of $600 in fines and fees, and a promise not to appear nude or partially nude in public for the next six months. (Latteier, 1998, p. 162) [At the time of Latteier's book publication in 1998, Sosnow was still facing appeals that were expected to last three to five years

(p. 162).

According to www.bodyobjective.com in a story by Peri Escarda accessed on April 7, 2003, Florida's 8th Circuit Court of Appeals Even before Sosnow's absurd experience in 1996, people had been fighting to eliminate the gender discrimination involved in her case. These feminists are proponents of Although equality between the sexes has long been an ideal throughout most of western society, very little attention has been paid to this area of striking discrimination. In order to delve into the gap between current topless laws and the fight against gender discrimination, it is important that the arguments on both sides of the issue are elucidated so as to encourage understanding and change. Therefore, this essay explores the main arguments for and against topfreedom circulating in the public sphere and groups them into rhetorical categories for future analysis.

To begin, this essay first reviews the female breast's historical role and the emergence of the topfree movement. Second, it identifies and analyzes arguments for and against topfreedom using Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca's (1969) work The New Rhetoric: A treatise on argumentation as a guide. Ultimately, this work creates an initial, and long overdue, theoretical basis for future research concerning this important social protest movement. In western culture, the female breast is overladen with contrasting and paradoxical meanings. The breast has consistently played a central role in the perception of women as divine idols, sexual deviants, consumers, mothers, citizens, employees, and medical patients. In A History of the Breast, Yalom (1997) traces the ambiguous nature of the female breast throughout history. On one hand, the breast has long been a symbol of spirituality and the sacred role of motherhood that is modeled after the Virgin Mary nursing the baby Jesus (p. 31). It has been said that as Mary provided nourishment for the divine child and is worthy of veneration, so are the nursing mothers who follow in her footsteps. This view is evident in the numerous paintings, sculptures, and other ancient and modern art works that feature the sacred act of a woman nursing her baby (p. 40). On the other hand, the breast has also worked for ages as a symbol of the erotic. Separated from the innocent divinity of the Virgin Mary, the display of the breast is associated with sexuality and carnal lust (p. 49). The erotic breast was, and continues to be, dominated by men. In this light, breasts are With this outlook, the Western world has adopted numerous alternatives to breastfeeding. Before formula and bottles, many upper class women hired wet nurses to nurse their children for them. By the late 18th century, wet nurses fed 90 percent of babies born in Paris, and other European urban areas boasted similarly high statistics (p. 106). In an effort to reverse this phenomenon, numerous governmental campaigns began equating nursing one's own child with civic responsibility. Yalom (1997) explains, As both Yalom and Latteier point out, the medical establishment has also become involved with the fight against breast cancer. Breast cancer has recently reached epic proportions with one in eight women in the United States contracting the disease in their lifetimes (American Cancer Society, 2002, p. 7). Treatment for breast cancer can include a harsh dose of chemotherapy, radiation, and a lumpectomy or mastectomy (Accad, 2001, p. 231). These methods have proven to be extremely effective in ridding the body of cancer and extending breast cancer patients' lives. Despite this reality, some people, including Accad (2001) in The Wounded Breast, hold that the removal of the breast is often an unnecessary procedure that contributes to the objectification and mistreatment of the female body (pp. 229-230). For this reason, increasing numbers of women with breast cancer are turning to alternative medicines in order to escape the sometimes harsh world of medical technology (Yalom, 1997, p. 276). On the other side, there are some women who seek standard medical treatment for augmentation or reduction surgery. Maine (2000) reports, The many historical and contemporary issues surrounding the female breast have framed the emergence of what Latteier (1998) labels The day on Coney Island in 1934 with which I opened this essay was one of the last instances where men had to fight for the right to go topfree in the western world, but it was just the beginning of women's battle to earn the same right. For instance, La Leche League was founded in 1956 and not only encouraged women to breast feed their children, an action that was frowned upon in the sexually repressed, sterile environment of the mid-20th century, but eventually defended women who nursed their babies and toddlers in public (Latteier, 1998, p. 154). To this day, La Leche League continues to play an active role in changing state obscenity laws that do not make exceptions for the exposure of nursing mothers. While the League was one of the earliest groups to support breast exposure, they have done so exclusively for the benefit of nursing mothers. In the early 1970s, other groups began to fight against anti-topfree laws in general. During this time, some women removed their shirts and bras as a statement against patriarchy and the objectification of the female breast (Yalom, 1997, p. 276; Latteier, 1998, p. 39). These women challenged anti-nudity clauses that include the female breast in the list of genitalia that must be covered in public (Hyde, 1997, p. 133). [Although the ordinances vary from state to state, most of them resemble one cited in a California case from 1975. Nudity is defined as displaying For the most part, such efforts were shot down in the courts. For instance, in 1975 a California judge ruled that because men and women's chests are biologically different, laws that limit only the exposure of women's breasts do not constitute sexual discrimination (p. 144). Similarly, in 1977 a Florida judge charged women with disorderly conduct for showing their breasts in public (Latteier, 1998, p. 161). Yet, the tides began to shift in favor of the topfree movement in 1992 with the case of People v. Santorelli. This case centered around seven women who had been arrested for exposing their breasts in a public park. The judge decided that there was no governmental interest at stake in requiring women to cover their breasts and that the breasts of both men and women are legally the same (Hyde, 1997, p. 144). Anti-topfree laws were thus eliminated in the state of New York, supporting the argument that While these recent successes in the effort to liberate the breast are encouraging, there are even more instances of governmental resistance to the topfree movement. Sosnow's experience is neither isolated nor exceptional. For instance, Evangeline Godron was arrested in August 1998 for swimming topfree in a city pool in Canada. This 64 year-old woman was literally carried out of the pool and charged with two counts of assault and one of mischief. She was then jailed for two days as a < q>threat to society.overturned Kayla Sosnow's disorderly conduct conviction’ three years and eight months after her initial arrest.]

(topfreedom,

which is the notion that women have the right to not wear a top in any situation that men also have that option

(Topfree!

2003). The same website explains, The word ‘topfree’ is used because it does not have the negative connotations of ‘topless’ in regard to commercial sex work.

The Female Breast'S Historical Role

offered up for the pleasure of a male… with the intent of arousing him, not her

(p. 90). Latteier (1998) tackles the breast's sacred and erotic role from a modern perspective. She identifies the ambiguity surrounding the female breast and the issue that brings this ambiguity to the forefront: breastfeeding. Latteier claims that with the modern day commercialization of the breast as a sexual object, breastfeeding has become a taboo: First, we do not trust the female body, and we feel squeamish about bodily secretions in general. Then, we value breasts for their erotic appeal. We believe that breasts should be attractive and that nursing wrecks

them. Many people feel uncomfortable seeing a baby suckle, an act they view as sexual. (p. 89)The nursing mother was seen as fulfilling her duty first to her family and then to the commonwealth

as she nourished its future citizens (p. 107). Today, Nadesan and Sotirin (1998) argue that the act of breastfeeding is still rich with ambiguous symbolism and that a new slant is brought to the mother/sexual-object dichotomy in the science of breast feeding

(p. 227). Science and medicine collapse the act into a normalized procedure that values the chemistry of the product, breast milk

(p. 227). Modern campaigns encourage breastfeeding by using slogans such as Breast is best,

which frame the female breast as an object of health, prosperity, and monetary profit (women who decide to breast feed are often encouraged by the medical community to purchase nursing pumps, specialized bras, and expensive nutritional supplements). In this light, the breast is not a symbol of motherhood or sexuality, but rather, simply a producer of a medically endorsed item for consumption, equivalent to a faucet or perhaps an assembly line part (p. 229).Between 1997 and 1998, nearly a quarter million American women risked general anesthesia, routine surgical complications, and known long-term side effects to [alter] their bust size

(p. 132). While those who get breast reduction surgery usually do so to take weight off of their backs and increase their mobility, women who risk the many side effects of breast implantation often have purely aesthetic aims (Yalom, 1997, p. 239). Clearly, the female breast has a long and many-sided history grounded in unrealistic expectations, symbolic power, and patriarchal control.The Emergence of the Topfree Movement

breast activism,

where individuals and groups encourage women to take the possession of their breasts away from the market economy (p. 153). Men were fighting for the right to go topfree in the United States until at least the mid-1930s (Heat,

1934, p. 3). [According to the Topfree Equal Rights Association

webpage, accessed on March 20, 2003, men continued to be arrested for going topless in other parts of the world such as South Africa.]the genitals, vulva, pubis, pubic, symphysis, pubic hair, buttocks, natal cleft, perineum, anus, anal region, or public hair region of any person, or any portion of the breast at or below the upper edge of the areola thereof the female person

(p. 133).]power, not nature, tells us when and whether a breast is a sexual organ

(p. 148). Similar decisions have since been made in places as diverse as the province of Ontario, Canada, the District of Columbia, and the state of Ohio. In addition, between 1995 and 1997, 12 states enacted laws that allow nursing mothers to feed their children in public (Latteier, 1998, p. 155).Woman's Choice,

2003)

Similarly, in New Jersey v. Vogt (2001) Arlene Vogt was charged $500 dollars for appearing topfree in a New Jersey public beach (Topfree Equal Rights Association,

2003). In 1997, the Topfree Equal Rights Association, TERA, was created to help women who encounter legal difficulty going without tops in public places in Canada

and to inform the public on the issue. It also helps women in the USA

(Topfree Equal Rights Association,

2003). Other groups including Women's Choice,

Topfreedom USA,

Right2Bare,

Topfree Equality for Women,

and Topfree!

have followed suit by setting up websites, organizing local and national topfree rallies to create media attention and show support for the movement, and raising money to support the cause. Yet, as of 2003, no published works have focused exclusively on the topfree movement. Thus, the following analysis of the primary arguments for topfreedom will be based on websites, newspaper coverage, and court records in the hopes of providing a starting point for research in this area. Before moving into the analysis, the next section of this essay introduces the analytical tools that will serve as a guide for this work.

The New Rhetoric

In 1969, an English translation of Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca's work The New Rhetoric: A treatise on argumentation introduced a compendium of methods of securing adherence, both argumentative schemes and stylistic resources

to a rhetorical tradition consumed by Cartesian logic (Conley, 1990, p. 298). Rather than limit their study of argumentative schemes to self-evident facts and logic, the authors developed a new rhetoric that is audience-centric, relying on logic as much as it does presumptions, values, and hierarchies (Perelman & Olbrechts-Tyteca, 1969, p. 2). Their goal was to characterize the different argumentative structures, the analysis of which must precede all experimental tests of their effectiveness

(p. 9). Thus, their argumentative schema

serves as a theoretical starting point in the search for the most efficacious way of affecting minds

(p. 8). These aims are appropriate in light of their definition of argumentation as the discursive means by which an audience is led to adhere to a given thesis, or by which its adherence is reinforced

(Conley, 1990, p. 297).

Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca's (1969) work serves as an appropriate guide for the following categorization and analysis of the topfree movement for several reasons. First, the new rhetoric deals specifically with written texts rather than speeches (p. 6). Until the topfree movement gains more credibility in the western world, written texts will be the primary vehicle for making its points. Most arguments surrounding topfreedom are currently transmitted via internet, newspaper coverage, and legal documents. Second, Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca wrote The New Rhetoric to serve as a theoretical starting point for future work in the arena of argumentation (p. 9). Similarly, groundwork needs to be laid for the debate surrounding the topfree movement in the way of categorizing argumentative schemes before other work on this topic can be accomplished. Third, Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca sought to uncover the entire range of discursive means of argumentation, not just the logical forms

(Conley, 1990, p. 297). In other words, they recognized the important role that arguments from value play in many areas of debate.

The arguments surrounding the issue of topfreedom are heavily value-laden, making this debate a case-in-point of what the new rhetoric aimed to include in its analysis of argumentation. Ultimately, this project does not seek to force The New Rhetoric's categories onto the arguments surrounding topfreedom but, rather, aims to follow in Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca's footsteps by identifying key argumentative schema and pointing out where similarities exist between the new rhetoric's categories and the arguments at hand. With any luck, this work will serve as a building block toward future experimental tests

that will distinguish the most effective arguments for topfreedom.

The Rhetoric Surrounding The Topfreedom Debate

After analyzing topfree websites, newspaper articles covering media events surrounding topfreedom, and court documents obtained by using the search engines Lexis-Nexis and Google, I have divided the primary arguments for topfreedom into the following categories: rhetoric of equality, rhetoric of sexuality, rhetoric of time, rhetoric of commerce, and rhetoric of health. I will look at each category by identifying arguments on both sides of the debate, giving a specific example for each side, and examining some of the theoretical assumptions underlying these arguments using The New Rhetoric as a guide.

Rhetoric Of Equality

First, the primary arguments surrounding the topfreedom debate deal with the rhetoric of equality. In most western societies, anti-topfree ordinances and court decisions tend to be grounded in the argument that men and women are inherently different and, therefore, laws must account for these differences. For instance, a few years after a group now called The Rochester Seven

began to protest for topless rights in New York, a guest columnist for USA Today criticized their goals, arguing, Bare-chested and bare-breasted are not the same,

and shouldn't be treated as if they are the same (Ellis, 1989, p. A8). On the other side, proponents of topfreedom make use of the tenets of liberal feminism and operate under the assumption that allowing men to go topless in the public sphere, but not women, is an example of inequality.

Topfree advocates argue that the following two claims are incompatible: 1) women and men have equal rights; 2) women are required to cover their chests in areas where men are allowed to go topfree. Specifically, the Right2bare

website explains, Despite a Constitution that espouses equal right for all Americans, laws defining nudity reflect a severe breach in gender equity. A topless woman is a criminal,

while a topless man in the same situation is functioning within his constitutional rights (2003). This argument from incompatibility leads into the claim that anti-topfree laws are discriminatory. The Topfreedom USA

website offers a case-in-point; it argues that laws against topfreedom are comparable to other practices that have been deemed discriminatory in the past:

To those who disagree, or feel that topfree equal rights are unimportant, consider how you would feel if our laws made it illegal for people of your race, or religion to remove your shirts in public, while people of other races, and religions remained free to do so. Imagine the police rushing in to a crowd to stop an African American from dressing like a white person. Imagine a Jew being fined, and forced to put on his shirt for trying to sunbathe like a Gentile. Imagine a woman being arrested for swimming in shorts like her husband. (2003)

Obviously, forcing a person of a certain race or religious belief to wear a shirt when other people are given the choice to do otherwise would be an act of discrimination. In this light, the word discrimination

is deemed an appropriate label for the application of anti-topfree ordinances that apply to only one gender.

The rhetoric of equality involves arguments from definition, the rule of justice,

and arguments from incompatibility. First, both sides of this debate make use of arguments from definition, a quasi-logical argument (Perelman & Olbrechts-Tyteca, 1969, p. 210). Those arguing against topfreedom define men and women as biologically different and, therefore, conclude that the genders' equal

treatment under the law will also have to be different as well. Advocates of topfreedom, on the other hand, begin their argument by defining anti-topfree laws as discriminatory. This argument from definition is based on what the new rhetoric calls the rule of justice

that requires giving identical treatment to beings or situations of the same kind

(Perelman & Olbrechts-Tyteca, 1969, p. 218). Here, the rule of justice

fits into what Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca label the rhetoric of incompatibility, another quasi-logical argument in which the theses one is disputing lead to an incompatibility, which resembles a contradiction in that it consists of two assertions between which a choice must be made, unless one rejects one or the other

(p. 196). In the case at hand, one must reject either the claim that women and men should be treated equally or the claim that women should be required to cover their chests in situations where men are not similarly restricted.

Rhetoric Of Sexuality

The rhetoric of sexuality is another category central to the topfreedom debate and involves two assumptions underlying anti-topfree ordinances and laws: women's breasts are inherently sexual and, therefore, allowing women to be topfree in the public sphere will lead to increased cases of sexual assault. Carol Faraone, the founder of Keep Tops On, an anti-topfreedom group, claims that topfreedom is walking pornography

and a practice that is degrading to women and would harm children

(Gillis, 1998, p. 05). Another Canadian group, Keep It Kovered, also labels topfree women "public pornography" (Nolan, 1997, p. A1). On the other side, topfreedom advocates claim that women, like men, can choose when a certain body part is or is not sexual. Women's breasts are not part of the human genitalia and, thus, are sexual only in the way that a woman's legs or arms are sexual. In other words: Different body parts arouse different people. Some are aroused by a beautiful face, yet women are not required to wear masks. Some are aroused by feet, yet women can wear sandals. Some aroused by legs, yet women can wear dresses or shorts. Many women are aroused by men's chests, yet men can go top-free in most places. (Topfree Equality for Women,

2001)

Similarly, children, it is argued, only get upset or bothered by something if they're taught to do so,

and given the fact that babies are nourished by breasts, it is ridiculous to claim that the sight of those same breasts are in any way harmful to children (Topfree Equality for Women,

2001). In response to the argument that allowing women to exercise topfreedom will lead to an increase in sexual assault cases, topfree advocates argue that men must take responsibility for their own actions. Ultimately, they assert, It's not a woman's task to prevent a man from harassing her, by wearing clothes men deem suitable on her! Women who wish to enjoy the same topfreedom as men are therefore not ‘asking for it’

(Topfree Equal Rights Association,

2003). The Topfreedom USA

website contributes to this argument by explaining:

Statistics show that Chinese women are raped more often than American women. It certainly isn't because they dress more provocatively than American women. It's because they aren't valued as equals by their society. Their value is disregarded, and their rights are denied. (2003)

Ultimately, topfreedom advocates claim that a woman's clothing choices do not automatically instigate men to violate them.

Several categories of argumentation underlie the rhetoric of sexuality: argument from definition, pragmatic argument, and the separation of the person from the act. Like the rhetoric of equality, both sides of the topfreedom debate utilizing the rhetoric of sexuality are guided by definition. The definitions of words such as breast,

genitalia,

pornography,

and indecency

serve both as starting points for the rhetoric of sexuality as well as points of contention. Arguments from definition often lead into pragmatic arguments, which allow a thing to be judged in terms of its present or its future consequences . . .

(Perelman & Olbrechts-Tyteca, 1969, p. 267). For instance, those against topfreedom first define exposed breasts as pornography,

then they deem the consequences of topfreedom, exposed breasts in the public sphere, to be unacceptable. Topfreedom advocates often use a similar argumentative pattern by first defining the female breast as a sexually neutral body part and then deeming topfreedom appropriate given the consequences of not doing so: the criminalization of a non-sexual act.

By claiming that topfree women will create an increase in sexual assault, those against topfreedom use an argument based on the separation of the person from the act

where an act is interpreted as a function of the person, and it is failure to respect this stability which is deplored when someone is reproached for incoherent or unjustified change

(Perelman & Olbrechts-Tyteca, 1969, p. 294). In this case, the person himself is separated from the act of sexual assault because it is, supposedly, part of his nature to commit this act at the sight of topfree women. In response, topfree advocates have chosen an existentialist argument by putting the accent on the freedom of the person, which places him in clear opposition to things

(p. 295). In other words, it is argued that men can choose to control themselves in situations where they are exposed to topfree women.

Rhetoric Of Time

Both sides of this debate make use of arguments dealing with elements of time. On one side, the supporters of antitopfree laws claim that because women are showing more skin than they ever have before, modern society is on a moral decline; the standards of the past are deemed superior to the standards of the present and the future. Howard Relin, a New York District Attorney, opposes topfreedom in an effort to maintain community standards

(Nolan, 1997, p. A1). Similarly, an Ottawa deputy mayor, Allan Higdon, contends that keeping female breasts covered is a common courtesy

and to do otherwise is thoughtless of the sensibilities of others

(Gillis, 1998, p. 05). Superior Court of New Jersey judge Wells in New Jersey v. Wells (2001) argues for the necessity of anti-topfree laws by noting that traditionally female breasts are unpalatable

for the eyes of the general public (Topfree Equal Rights Association,

2003).

Contrarily, advocates of topfreedom claim that women are finally on the verge of a liberation that has never been available to them in the past. Over time, the covering of female body parts such as legs and arms has, for the most part, been deemed unnecessary and repressive. The Women's Choice

website argues: Let`s go to recent history for a moment: until 70 or so years ago, women couldn't even show their ankles — for the same reason, that they are different.

For centuries and centuries women had to wear skirts that were ankle length (just imagine walking in that your whole life!). Today, women in western culture can wear miniskirts showing even

their knees — unimaginable for women before some 70 years ago. And, what happened? NOTHING. (2003, emphasis in original)

This website also claims that if our decisions were always based on what has been the norm in the past, nothing would ever change. Slavery and other discriminatory activities would still be legal.

Clearly, the rhetoric of topfreedom is appealing to the future, while the rhetoric of anti-topfreedom is appealing to the past. The latter is making use of what Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca (1969) label the loci of order,

which affirms the superiority of that which is earlier over that which is later

(p. 93). This argument can also be understood in light of the device of stages,

commonly referred to as the slippery slope

argument, where the reasoning is described as follows: if you give in this time, you will have to give in a little more next time, and heaven knows where you will stop

(p. 282). In other words, as society has accepted women wearing less clothing over time, debauchery triumphs over morality. Topfreedom is yet another step in the wrong direction. Topfree proponents see things the other way around and appeal to arguments with unlimited development

that: insist on the possibility of always going further in a certain direction without being able to foresee a limit to this direction, and this progress is accompanied by a continuous increase of value

(p. 287). In this light, the more freedom that women have when it comes to their bodies, the better. Topfreedom is another sign of progress.

Rhetoric Of Commerce And Health

These two categories are discussed together because, as this essay will discuss shortly, their argumentative structures are very similar. First, the marketplace is another point of contention in the topfreedom debate creating a rhetoric of commerce. Generally, the conventions of business and capitalism require that exposed female breasts be strictly regulated and restricted to certain areas. A guest columnist for USA Today makes this claim by explaining, In all of life, rules and discipline are necessary

(Ellis, 1989, p. A8). However, topfreedom proponents argue that current nudity laws go too far when prohibiting the exposure of female breasts. Breasts are treated like a commodity, they say, and, as a result, women do not have control over their own breasts (Topfree Equal Rights Association,

2003). In the spirit of Marxist feminism, or what Donovan (1992) labels socialist feminism and describes as the belief that women are oppressed by the combination of modern economic concerns and patriarchy, they identify a hypocrisy in the regulation of female breasts when topless bars, the pornography industry, and the world of advertising profit from the breast's exploitation. The Right2bare

website claims that topfreedom is about women owning their own bodies rather than having them rented out by corporations as highly valuable marketing tools

(2003). The Right2bare

website also reports:

They tell us to flaunt all the skin we possibly can — but not too much. What would happen to the pornography industry — magazines, clubs, internet — if women were free to walk around topless in a park or down the street? Our breasts would lose their magical marketability. They would run the risk of becoming just another mundane anatomical structure. Corporations would lose our bodies as tools to sell us everything from cars to cigarettes. (2003)

Second, in light of the rhetoric of health, while those who support anti-topfree laws generally do not recognize a correlation between women's health and the regulation of their breasts, topfreedom supporters draw several conclusions about how these rules are detrimental to women's wellbeing. Some argue that requiring women to cover their breasts in situations where men are not required to do so teaches women that their bodies are unacceptable and objects of which they should be ashamed. This effect is only exacerbated when the breasts that are highlighted in the media belong primarily to young, extremely toned models. Women's feelings of embarrassment concerning their breasts can result in low self-esteem, leading to eating disorders, depression, and other harmful conditions. For instance, the Topfree Equality for Women

website explains:

A grandmother of the author of this page had such a poor self-image and was afraid to have someone look at her body that she delayed going to a doctor until the cancer that she was suffering from had gone too far to be treated, and she died as a result. (2001)

Correspondingly, it is argued that when women are ashamed of their breasts, they are less likely to breastfeed their children, possibly compromising the health of their offspring as well as their own health. In these final two categories, both the rhetoric of commerce and the rhetoric of health, Perelman and Olbrechts- Tyteca's (1969) concept of presence

is especially pronounced. Presence

relies on the fact that all argumentation is selective

(p. 119). Thus, by the very fact of selecting certain elements and presenting them to the audience, their importance and pertinency to the discussion is implied

(p. 116). The concept of presence

is easy to spot in these two categories of argumentation because they discuss elements of the topfreedom debate that might not be immediately apparent to an uninitiated individual: the commercialization of the breast and the health consequences of anti-topfree laws. These arguments illustrate a specific structure of reality

highlighting aspects of that reality that the authors wish to promote

(p. 261). In the case of the rhetoric of commerce and the rhetoric of health, topfreedom advocates are drawing causal links (i.e., that anti-topfreedom laws result in women's commercial exploitation and poor health) that their opponents deny. They know that the same event will be interpreted, and differently evaluated, according to the idea formed of the nature — intended or involuntary — of its consequences

(p. 270-271). Therefore, they have put forth arguments that feature consequences the public might not explore by itself.

Conclusions

Although topfreedom has a fairly long history in the western world, it continues to be an issue that receives little thoughtful consideration or attention from the general public. In fact, while discussing the project at hand with others, I found that upon hearing a brief synopsis of the topfreedom movement's goals, most people dismiss the idea that women should be allowed to go topfree whenever men are given the choice to do so as ludicrous. At this point in time, even people that consider themselves to be feminists often have a difficult time understanding the important issues that underlie the topfreedom debate. In this light, it is apparent that arguments for topfreedom must be thoughtful, purposive, and audience-centered in order to gain the consideration of an uninitiated public. While it might be easy to create a media event featuring bare breasted ladies,

the title itself reminiscent of a circus act, it is not so easy to get the public to take those same ladies' concerns seriously.

This essay seeks to begin the process of crafting argumentation that will bring the topfreedom movement forward by providing a theoretical starting point for the discovery of, as Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca (1969) put it, the most efficacious way of affecting minds

to the issues surrounding topfreedom (p. 8). Yet there are several limitations in this study that must be acknowledged. First, I have identified the five primary categories of argumentation surrounding topfreedom as the rhetoric of equality, rhetoric of sexuality, rhetoric of time, rhetoric of commerce, and rhetoric of health. However, there are also many secondary arguments surrounding the topfreedom debate that have yet to be addressed but are beyond the scope of this essay.

Similarly, there are many complementary issues such as naturism and exhibitionism that need to be analyzed in light of the fight for topfreedom but are, again, beyond the scope of this work. Second, more emphasis has been placed on the arguments for topfreedom than the arguments against topfreedom in this essay. However, this is less of a biased oversight than a response to the number of anti-topfreedom arguments circulating in the public sphere. Currently, because the status quo has not been in danger, arguments supporting these laws are few and far between. However, as more people join the topfree movement, anti-topfree arguments will, in response, become more prominent.

Clearly, the topfreedom movement is ripe with research opportunities. Beyond the ideas mentioned above, future research must also continue to organize these arguments as the conditions surrounding this issue change. Perhaps most importantly, scholars will need to build from these theoretical categories to decide which arguments best interact with and inform audiences in various situations. Equal attention must be paid to the arguments that uphold anti-topfree laws and ordinances so that we can both understand them and respond to them. Ultimately, topfreedom as an idea is making its way into the agenda of public discourse and must continue on that path in order to achieve the important goals that it upholds.

References

- Accad, E. (2001). The wounded breast. Chicago: University of Illinois.

- American Cancer Society. Breast cancer: facts & figures 2001-2002. (2002). Atlanta, Georgia: ACS.

- Ayalah, D., & Weinstock, I.J. (1979). Breasts: Women speak about their breasts and their lives. New York: Summit Books.

- Conley, T. (1990). Rhetoric in the European tradition. Chicago: University of Chicago.

- Donovan, J. (1992). Feminist theory: the intellectual traditions of American feminism, 2nd ed. New York: Continuum.

- Ellis, T. (1989, July 6). "Face-off: Going bare-chested; Good taste is not discrimination." USA Today, p. A8.

- Gillis, M. (1998, July 5). "Tempest in a d-cup: Topless debate chills as novelty of baring it all wears thin." The Ottawa Sun, p. 05.

- "Heat of 89.3 Degrees Ushers in Summer" (1934, June 22). The New York Times, p. 3.

- Hyde, A. (1997). Bodies of law. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

- Latteier, C. (1998). Breasts: The woman's perspective on an American obsession. New York: Harrington Park Press.

- Maine, M. (2000). Body wars: making peace with women's bodies. Carlsbad, CA: Gurze Books.

- Nolan, M.K. (1997, August 11). "Topless women? Not in conservative Hamilton." Hamilton Spectator, p. A1.

- Perelman, C., & Olbrechts-Tyteca, L. (1969). The New Rhetoric: A treatise on argumentation (J. Wilkinson & P.

- Weaver, Trans.). Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame. (Original work published 1958) Right2Bare. (2003). Retrieved April 17, 2003, from http://right2bare.tripod.com/right2bare/index.html

- Topfree Equal Rights Association. (2003). Retrieved April 1, 2003, from http://www.tera.ca/index.html

- Topfree Equality for Women. (2001). Retrieved March 22, 2003, from http://www.ohnuderec.org/Topfree/tf.html

- Topfree! (2003). Retrieved March 20, 2003, from http://www.topfreedom.com/index.html

- Topfreedom USA. (2003). Retrieved April 2, 2003, from http://www.topfreedomusa.0catch.com

- Women's Choice. (2003). Retrieved April 15, 2003, from http://www.geocities.com/womens_choice_org/topfreedom.html

- Yalom, M. (1997). The history of the breast. New York: Knopf.

© 2003 by Robin E. Jensen, Reprinted with Permission